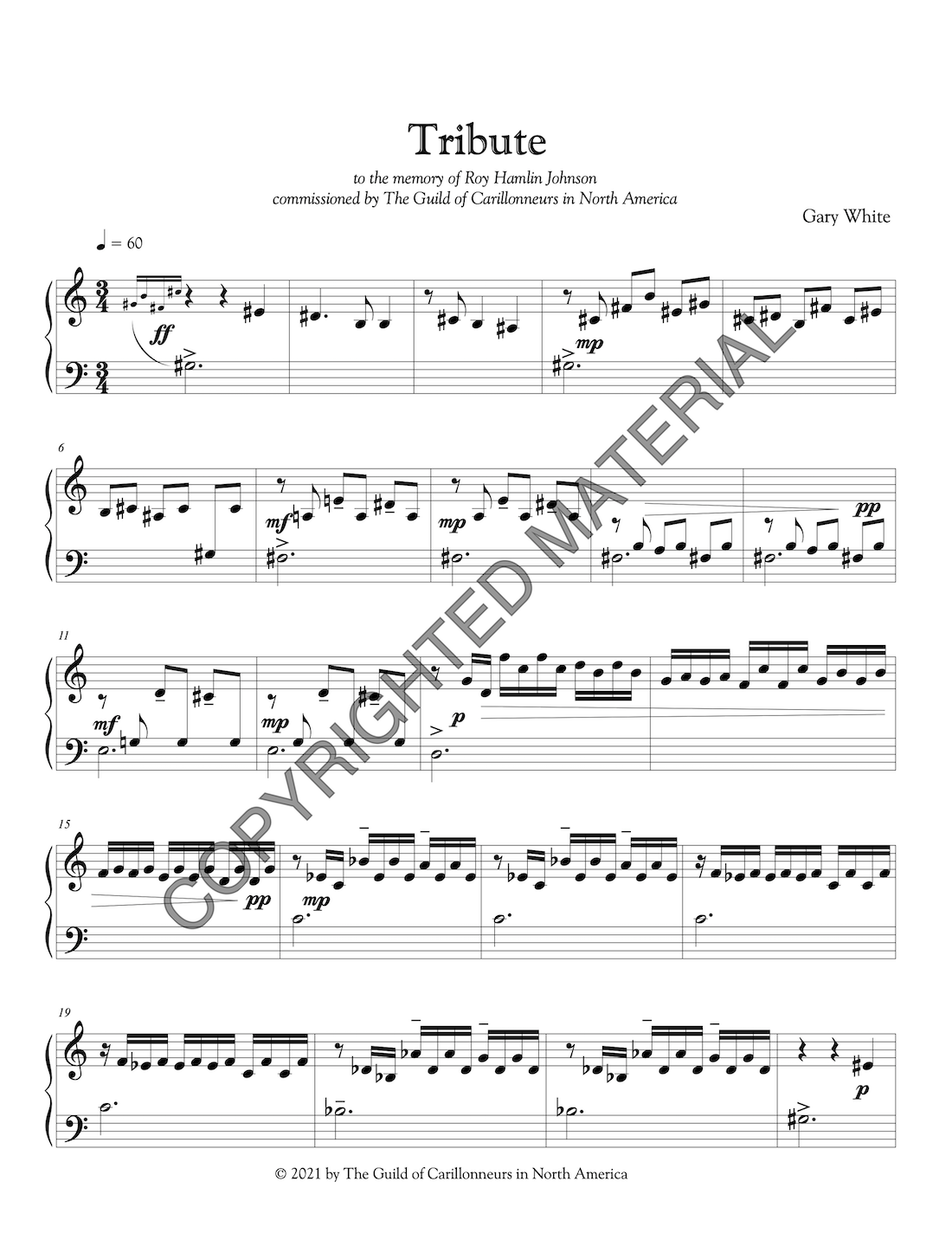

Tribute

Commissioned by the Johan Franco Composition Fund of The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America to the memory of Roy Hamlin Johnson

1955–1959: A Very Special Time for the Carillon at the University of Kansas

These are my "carillon related" reminisces from when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Kansas, from 1955 to 1959, and the years after. I went to KU to study to become a public-school music teacher. Although I had studied piano as a child and spontaneously written small compositions for my piano teacher at age eight, I had become much more interested in playing the trumpet and developing my voice. I planned to become a high-school band director like my high-school band director and hero, George Beggs.

As a music education student, I was required to study the piano and pass a piano proficiency exam. The faculty at KU realized that, as teachers, we would be using the keyboard every day, so we needed minimum skills. Members of the university piano faculty were required to prepare a certain number of non-pianists for the piano proficiency examination. I was assigned to Roy Hamlin Johnson. This was a fortuitous event for my future as a serious composer because Roy was not only a brilliant concert pianist, he also had an interest in composing.

He quickly realized that I had similar interests and talents, and he assigned the Bartók Mikrokosmos pieces for me to play and for us to study for their musical structure. We had many delightful conversations about the wonders of those small pieces, and my lessons with him were a pure joy. It was during those lessons that I became convinced that being a composer was much more interesting than being a band director, and I decided to pursue a double major in music education and composition.

I barely passed my piano proficiency exam, in part because Roy and I spent so much time talking about the structure of music and analyzing the Bartók Mikrokosmos pieces! However, that time was critical for my future as a composer and music theorist. I owe Roy Hamlin Johnson a huge debt of gratitude for his role in showing me the life path that I pursued for the rest of my career. It is an honor for me to be able to repay that debt in some small way with Tribute, the piece the GCNA has commissioned me to compose in his honor.

The university carillonneur at KU, Ronald Barnes, was constantly in search of people to write for the instrument. He had recruited Roy to write Summer Fanfares in 1956, while I was studying piano with him. Roy and I had many conversations about the peculiarities of the bells and how to use them to advantage in a composition. He illustrated our conversations with his score to Summer Fanfares. That was how I came to understand what music for carillon looked and sounded like. I never thought, however, that I would actually compose for the instrument.

It was just after the Kansas City Philharmonic performed my first orchestral piece that Ron Barnes approached me in the hall of the KU music building and complemented me on my talent as a composer. He had been in the audience for the performance. He asked, "Would you like to write for an instrument where your music will be played for a long time in the future? If so, write for the carillon!"

I was intrigued by the challenge and, having studied the score of Summer Fanfares with Roy, I undertook to write something for the instrument. The result was Prelude and Fugue for Carillon, which Ron premièred on the KU carillon. I then wrote the Three Short Pieces over the next few years, while I was the band director in the public schools of Dolores, Colorado. I mailed them to Ron, who was by that time carillonneur at the National Cathedral. He premièred them in Washington, D.C., and sent me copies of the programs. It was several years before I heard those pieces played on the carillon because there was no carillon within hundreds of miles of Dolores, Colorado.

I want to insert an interesting aside here. When I decided to pursue a PhD in composition, I was awarded a teaching assistantship at Michigan State University in Lansing. I approached the university carillonneur, Wendell Westcott, with my little pieces and asked him to play them so I could finally hear them. He took one look and declined to even read through them. I was disappointed, but Westcott was a peculiar character and he gave me no reason for turning me down. It was only when I accepted a position on the faculty of Iowa State University in 1967 that ISU carillonneur Ira Schroeder added them to his repertoire. I finally heard those short pieces played on the Stanton Memorial Carillon at Iowa State. The sound of the Iowa State carillon is what I have had in mind while composing all my other carillon pieces.

Ron Barnes's prediction that writing for carillon would ensure that my music would be played for a long time has come to pass. When I receive my royalty checks from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP), it is the carillon works that inevitably show the most performances. I am grateful to The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America, both for their continued performance of my music and for the commission that gave me the opportunity to write Tribute in honor of Roy Hamlin Johnson, my piano teacher, my inspiration to become a composer, and my lifelong friend.

—Gary C. White

E-sharp, Why E-sharp?

When Joey Brink contacted me offering a commission from The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America to write a composition in honor of the memory of Roy Hamlin Johnson, at first, I wondered if I could still compose anything after a hiatus of some 26 years. I said I would think about it and get back with him.

I gave the project considerable thought and came to the conclusion that I could and would do it. However, Tribute isn't "to the memory of Roy Hamlin Johnson," in spite of what is printed on the cover of the score. I wrote it for Roy—for us to enjoy and have a good laugh over somewhere when our souls meet on the other side of death. (I am so sure that human consciousness survives death that I am increasingly looking forward to my adventures in that realm.)

I told Joey I would fulfill the commission, but it would need to be after more months than the Guild had in mind. I was deeply involved in several other projects and needed to finish them first. So, as I worked on my latest book, The Dowsing Mind: Into the Multi-Dimensional Realms and Back, the thought of what Roy and I might get a kick out of someday was forming in my mind. (If you want to get a picture of what our friendship was like, read the short article that accompanies the score.)

The first laugh that we will share is the title of this article. You may wonder why I chose in the composition to write E-sharp rather than F. I hope that will become clear, and I'm sure Roy and I will share a laugh about that one when we next meet.

One thing I learned from Roy was a deep appreciation for the structures that lie hidden in all good music. He delighted in how the little pieces in Bartók's Mikrokosmos were all beautifully organized and thoroughly thought through. The absolute delight in his eyes as he revealed to me, a 19-year-old kid from a small town on the Oklahoma border, how Bartók had structured those little pieces convinced me that I wanted to compose something like that someday. And that is exactly what I have tried to do in over 40 years of composing.

So, what was I going to embed in this piece in honor of Roy? I thought that something about our place of meeting—The University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas—would do nicely. How about the "Alma Mater" for KU? That is a piece of music that could be quoted in this piece. If I simply quoted it, that would be too obvious. But if only a few snippets were used I might be able to hide them in plain sight. I thought of the tune in B-flat major and collected all the pitches of the B-flat major scale in my head.

Since I had not been composing for the past 26 years, I had no music paper to write on, and I had long since stopped carrying a functioning piano keyboard around with me. I had a small MIDI keyboard that I had connected to my computer 11 years before, but I had not tried to connect it to my current computer. I found a PDF of music paper online and printed out a supply. Getting the ancient MIDI keyboard connected was more challenging, but I found a patch cord online and ordered it. While I waited for the patch cord, I began sketching the musical ideas that had been running around in my head.

B-flat seemed too obvious to me so I chose g minor, the relative minor of B-flat major. The tune would not be so obvious if it occurred in the context of a minor key. That's what I took into "dreamtime"—the g minor scale. Most of my composing comes in day or night dreaming and this was no exception. I woke up with several ideas running around in my head, and very soon I had a few sketches of what seemed like promising musical ideas.

Now comes the critical moment for the whole project. When I had the patch cord and, for the first time, a keyboard that would produce sound I sat down to play over the sketches I had noted down on music paper. In playing them over, my finger seemed to slip and I played E-natural rather than the E-flat I had written. That E-natural was very interesting and I instantly knew that it was right. (Roy, did you nudge my finger ever so slightly to tell me what would make the piece more interesting?) That slight chromatic shift gave me ideas for how to proceed and I took the new direction back into dreamtime. Interesting musical ideas came easily and the next morning I was off and running.

Instead of the B-flat major scale I now noticed that the E-natural made it into the beginning of the whole tone scale: B-flat, C, D, and E. Furthermore, when I began to put the fragments together, a descending whole tone scale began to emerge in the bass: G, F, E-flat, D-flat. Wait! The carillon doesn't usually have the low D-flat or, sometimes, not even the E-flat. What to do? I obviously had to transpose the piece to fit the instru- ment. If I transposed it up a half-step I would get around the problem. So, instead of g minor I had either g-sharp minor or a-flat minor. A-flat minor has 7 flats, but g-sharp minor has only 5 sharps, much better. But now, what to do about the E-natural? It would become E-sharp. Well, a-flat minor would have an F-flat and a C-flat, so g-sharp minor was still better. And that E-sharp would stand as a little symbol of that moment when Roy shifted my finger ever so slightly! Yes, I left the E-sharp as a little marker of Roy's contribution to Tribute. Carillonneurs will just have to live with it. If it causes you too much trouble, just write F above the E-sharps and you won't miss!

So now, when you play Tribute you will notice that descending whole-tone scale in the bass: G-sharp, F-sharp, E, D, and then at the very end of the piece, C. So, what happened to KU's Alma Mater? In measures 67 and 68 you will find a short quote with the notes marked with accents. That is where KU's Alma Mater comes through for just a moment. When you play those measures picture the delight in Roy Johnson's eyes. And in my eyes, too!

—Gary C. White

![[PDF] Tribute [PDF] Tribute](https://d2j6dbq0eux0bg.cloudfront.net/images/9481258/2306646161.jpg)